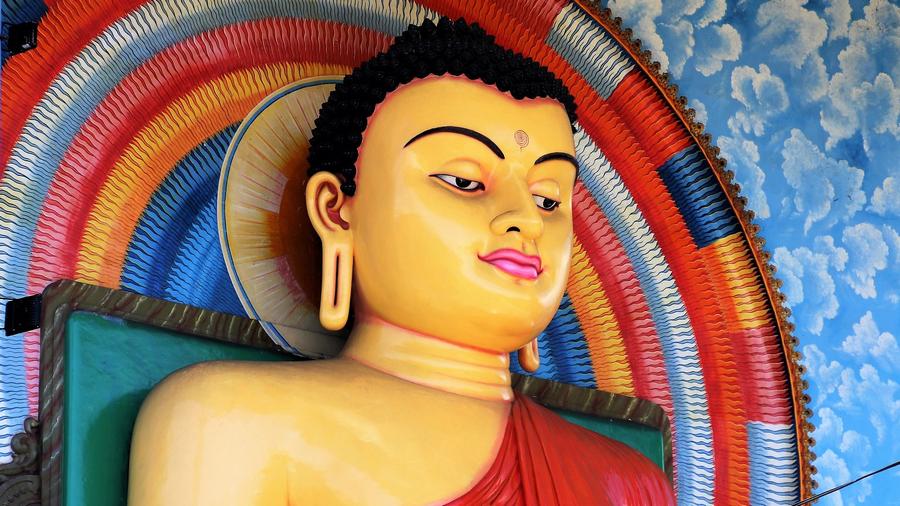

[Note: In this very deep and profound sutta the Buddha ties disputes to the process of dependent origination. Three other translations are linked to below.]

“Where do quarrels and disputes come from?

And lamentation and sorrow, and stinginess?

What of conceit and arrogance, and slander too—

tell me please, where do they come from?”

“Quarrels and disputes come from what we hold dear,

as do lamentation and sorrow, stinginess,

conceit and arrogance.

Quarrels and disputes are linked to stinginess,

and when disputes have arisen there is slander.”

“So where do things held dear in the world spring from?

And the lusts that are loose in the world?

Where spring the hopes and aims

a man has for the next life?”

“What we hold dear in the world spring from desire,

as do the lusts that are loose in the world.

From there spring the hopes and aims

a man has for the next life.”

“So where does desire in the world spring from?

And judgments, too, where do they come from?

And anger, lies, and doubt,

and other things spoken of by the Ascetic?”

“What they call pleasure and pain in the world—

based on that, desire comes about.

Seeing the appearance and disappearance of forms,

a person forms judgments in the world.

Anger, lies, and doubt—

these things are, too, when that pair is present.

One who has doubts should train in the path of knowledge;

it is from knowledge that the Ascetic speaks of these things.”

“Where do pleasure and pain spring from?

When what is absent do these things not occur?

And also, on the topic of appearance and disappearance—

tell me where they spring from.”

“Pleasure and pain spring from contact;

when contact is absent they do not occur.

And on the topic of appearance and disappearance—

I tell you they spring from there.”

“So where does contact in the world spring from?

And possessions, too, where do they come from?

When what is absent is there no possessiveness?

When what disappears do contacts not strike?”

“Name and form cause contact;

possessions spring from wishing;

when wishing is absent there is no possessiveness;

when form disappears, contacts don’t strike.”

“Form disappears for one proceeding how?

And how do happiness and suffering disappear?

Tell me how they disappear;

I think we ought to know these things.”

“Without normal perception or distorted perception;

not lacking perception, nor perceiving what has disappeared.

Form disappears for one proceeding thus;

for concepts of identity due to proliferation spring from perception.”

“Whatever I asked you have explained to me.

I ask you once more, please tell me this:

Do some astute folk here say that this is the highest extent

of purification of the spirit?

Or do they say it is something else?”

“Some astute folk do say that this is the highest extent

of purification of the spirit.

But some of them, claiming to be experts,

speak of a time when nothing remains.

Knowing that these states are dependent,

and knowing what they depend on, the inquiring sage,

having understood, is freed, and enters no dispute.

The wise do not proceed to life after life.”

Read this translation of Snp 4.11 Kalahavivādasutta: Quarrels and Disputes by Bhikkhu Sujato on SuttaCentral.net. Or read a different translation on SuttaCentral.net, DhammaTalks.org or AccessToInsight.org. Or listen on SC-Voice.net. Or explore the Pali on DigitalPaliReader.online.

Or read a translation in Afrikaans, Deutsch, Français, Indonesian, Italiano, မြန်မာဘာသာ, Nederlands, Norsk, Português, ру́сский язы́к, සිංහල, Slovenščina, Svenska, or தமிழ். Learn how to find your language.