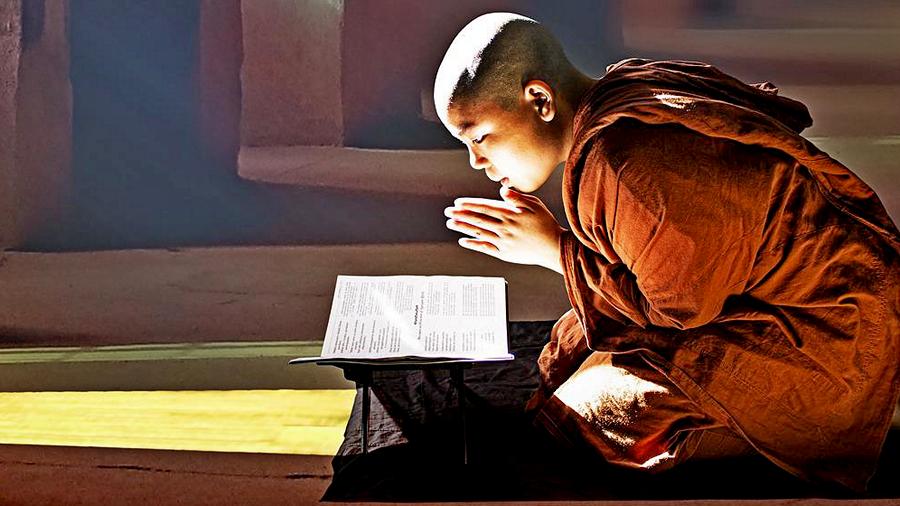

“Monks, when the teachings have been followed by ear, recited by speech, examined by mind, and well penetrated by view, four rewards can be expected. Which four?

“There is the case where a monk has mastered the Dhamma: dialogues, narratives of mixed prose & verse, explanations, verses, spontaneous exclamations, quotations, birth stories, amazing events, question & answer sessions (i.e. the earliest classifications of the Buddha’s teachings). In him, these teachings have been followed by ear, recited by speech, examined by mind, and well penetrated by view. Passing away when his mindfulness is muddled, he arises in a certain group of devas. To him, happy there, they recite verses of Dhamma. Slow is the arising of his mindfulness, but when mindful, he quickly arrives at distinction. When the teachings have been followed by ear, recited by speech, examined by mind, and well penetrated by view, this is the first reward that can be expected.

“Further, there is the case where a monk has mastered the Dhamma: dialogues… question & answer sessions. In him, these teachings have been followed by ear, recited by speech, examined by mind, and well penetrated by view. Passing away when his mindfulness is muddled, he arises in a certain group of devas. It doesn’t happen that they recite verses of Dhamma to him, happy there. But a monk with psychic power, attained to mastery of awareness, teaches the Dhamma to the assembly of devas. The thought occurs to the new deva: ‘This is the Dhamma & Vinaya under which I used to live the holy life.’ Slow is the arising of his mindfulness, but when mindful, he quickly arrives at distinction.

“Suppose a man skilled in the sound of a war drum were to hear the sound of a war drum while traveling along a highway. He would have no doubt or perplexity, ‘Is that the sound of a war drum or not the sound of a war drum?’ He would come to the conclusion, ‘That’s the sound of a war drum for sure.’ In the same way, there is the case where a monk has mastered the Dhamma.… Passing away when his mindfulness is muddled, he arises in a certain group of devas.… A monk with psychic power, attained to mastery of awareness, teaches the Dhamma to the assembly of devas. The thought occurs [to the new deva]: ‘This is the Dhamma & Vinaya under which I used to live the holy life.’ Slow is the arising of his mindfulness, but when mindful, he quickly arrives at distinction. When the teachings have been followed by ear, recited by speech, examined by mind, and well penetrated by view, this is the second reward that can be expected.

“Further, there is the case where a monk has mastered the Dhamma: dialogues… question & answer sessions. In him, these teachings have been followed by ear, recited by speech, examined by mind, and well penetrated by view. Passing away when his mindfulness is muddled, he arises in a certain group of devas. It doesn’t happen that they recite verses of Dhamma to him, happy there. Nor does a monk with psychic power, attained to mastery of awareness, teach the Dhamma to the assembly of devas. But a deva teaches the Dhamma to the assembly of devas. The thought occurs to the new deva: ‘This is the Dhamma & Vinaya under which I used to live the holy life.’ Slow is the arising of his mindfulness, but when mindful, he quickly arrives at distinction.

“Suppose a man skilled in the sound of a conch were to hear the sound of a conch while traveling along a highway. He would have no doubt or perplexity, ‘Is that the sound of a conch or not the sound of a conch?’ He would come to the conclusion, ‘That’s the sound of a conch for sure.’ In the same way, there is the case where a monk has mastered the Dhamma.… Passing away when his mindfulness is muddled, he arises in a certain group of devas.… A deva teaches the Dhamma to the assembly of devas. The thought occurs to the new deva: ‘This is the Dhamma & Vinaya under which I used to live the holy life.’ Slow is the arising of his mindfulness, but when mindful, he quickly arrives at distinction. When the teachings have been followed by ear, recited by speech, examined by mind, and well penetrated by view, this is the third reward that can be expected.

“Further, there is the case where a monk has mastered the Dhamma: dialogues… question & answer sessions. In him, these teachings have been followed by ear, recited by speech, examined by mind, and well penetrated by view. Passing away when his mindfulness is muddled, he arises in a certain group of devas. It doesn’t happen that they recite verses of Dhamma to him, happy there. Nor does a monk with psychic power, attained to mastery of awareness, teach the Dhamma to the assembly of devas. Nor does a deva teach the Dhamma to the assembly of devas. But another spontaneously-arisen being reminds this spontaneously-arisen being, ‘Do you remember, my dear? Do you remember where we practiced the holy life together?’ He says, ‘I remember, my dear. I remember.’ Slow is the arising of his mindfulness, but when mindful, he quickly arrives at distinction.

“Suppose that there were two comrades who played together in the mud. They would happen to meet later at some time, at some place, and there one companion would say to the other, ‘Do you remember this, my friend? And do you remember this?’ And the other would say, ‘I remember, my friend. I remember.’ In the same way, there is the case where a monk has mastered the Dhamma: dialogues… question & answer sessions. In him, these teachings have been followed by ear, recited by speech, examined by mind, and well penetrated by view. Passing away when his mindfulness is muddled, he arises in a certain group of devas.… A spontaneously-arisen being reminds this spontaneously-arisen being, ‘Do you remember, my dear? Do you remember where we practiced the holy life together?’ He says, ‘I remember, my dear. I remember.’ Slow is the arising of his mindfulness, but when mindful, he quickly arrives at distinction. When the teachings have been followed by ear, recited by speech, examined by mind, and well penetrated by view, this is the fourth reward that can be expected.

“Monks, when the teachings have been followed by ear, recited by speech, examined by mind, and well penetrated by view, these four rewards can be expected.”

Read this translation of Aṅguttara Nikāya 4.191 Sotānugata Sutta. Followed by Ear by Bhikkhu Ṭhanissaro on DhammaTalks.org. Or read a different translation on SuttaCentral.net. Or listen on PaliAudio.com or SC-Voice.net. Or explore the Pali on DigitalPaliReader.online.

Or read a translation in Deutsch, বাংলা, Français, Bahasa Indonesia, 日本語, မြန်မာဘာသာ, Русский, සිංහල, ไทย, Tiếng Việt, or 汉语. Learn how to find your language.

Translations by Bhikkhu Ṭhanissaro are released under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 Unported License. The author considers any sale, including by non-profit entities for non-profit purposes, to be ‘Commercial’ and a copyright violation. To view a copy of this license, visit the

Translations by Bhikkhu Ṭhanissaro are released under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 Unported License. The author considers any sale, including by non-profit entities for non-profit purposes, to be ‘Commercial’ and a copyright violation. To view a copy of this license, visit the

Copyright: Creative Commons Zero (CC0) To the extent possible under law, Bhikkhu Sujato has waived all copyright and related or neighboring rights to his own translations on

Copyright: Creative Commons Zero (CC0) To the extent possible under law, Bhikkhu Sujato has waived all copyright and related or neighboring rights to his own translations on

All translations on this site by Bhikkhu Bodhi are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.

Bhikkhu Bodhi, The Middle Length Discourses of the Buddha (Wisdom Publications, 2009), The Connected Discourses of the Buddha (Wisdom Publications, 2000), The Numerical Discourses of the Buddha (Wisdom Publications, 2012).

All translations on this site by Bhikkhu Bodhi are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.

Bhikkhu Bodhi, The Middle Length Discourses of the Buddha (Wisdom Publications, 2009), The Connected Discourses of the Buddha (Wisdom Publications, 2000), The Numerical Discourses of the Buddha (Wisdom Publications, 2012).