[Note: This is a slightly longer selection for the weekend. The entire sutta is good to read if you have time.]

Thus have I heard. On one occasion the Blessed One was living in the Sakyan country at Sāmagāma.

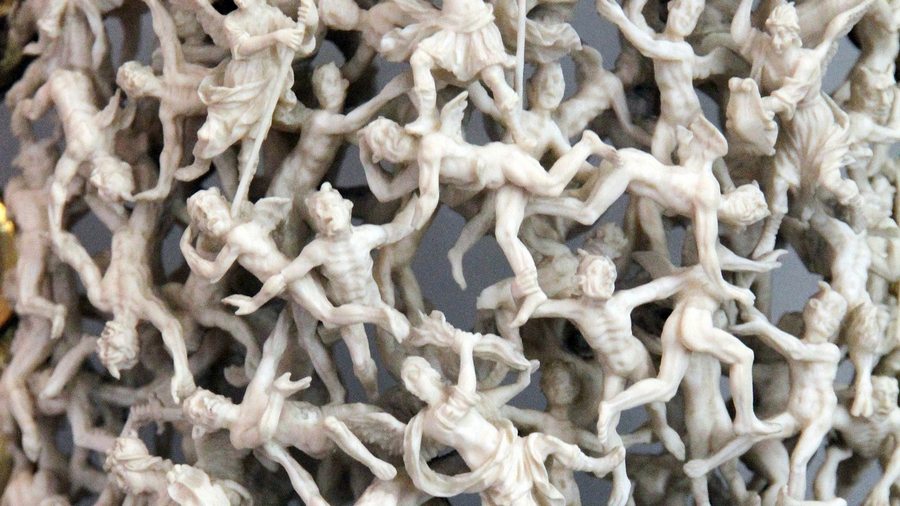

Now on that occasion the Nigaṇṭha Nātaputta had just died at Pāvā. On his death the Nigaṇṭhas divided, split into two; and they had taken to quarrelling and brawling and were deep in disputes, stabbing each other with verbal daggers: “You do not understand this Dhamma and Discipline. I understand this Dhamma and Discipline. How could you understand this Dhamma and Discipline? Your way is wrong. My way is right. I am consistent. You are inconsistent. What should have been said first you said last. What should have been said last you said first. What you had so carefully thought up has been turned inside out. Your assertion has been shown up. You are refuted. Go and learn better, or disentangle yourself if you can!” It seemed as if there were nothing but slaughter among the Nigaṇṭha Nātaputta’s pupils. And his white-clothed lay disciples were disgusted, dismayed, and disappointed with the Nigaṇṭha Nātaputta’s pupils, as they were with his badly proclaimed and badly expounded Dhamma and Discipline, which was unemancipating, unconducive to peace, expounded by one not fully enlightened, and was now with its shrine broken, left without a refuge.

Then the novice Cunda, who had spent the Rains at Pāvā, went to the venerable Ānanda, and after paying homage to him, he sat down at one side and told him what was taking place.

The venerable Ānanda then said to the novice Cunda: “Friend Cunda, this is news that should be told to the Blessed One. Come, let us approach the Blessed One and tell him this.”

“Yes, venerable sir,” the novice Cunda replied.

Then the venerable Ānanda and the novice Cunda went together to the Blessed One. After paying homage to him, they sat down at one side, and the venerable Ānanda said to the Blessed One: “This novice Cunda, venerable sir, says thus: ‘Venerable sir, the Nigaṇṭha Nātaputta has just died. On his death the Nigaṇṭhas divided, split into two…and is now with its shrine broken, left without a refuge.’ I thought, venerable sir: ‘Let no dispute arise in the Sangha when the Blessed One has gone. For such a dispute would be for the harm and unhappiness of many, for the loss, harm, and suffering of gods and humans.’”

“What do you think, Ānanda? These things that I have taught you after directly knowing them—that is, the four foundations of mindfulness, the four right kinds of striving, the four bases for spiritual power, the five faculties, the five powers, the seven enlightenment factors, the Noble Eightfold Path—do you see, Ānanda, even two bhikkhus who make differing assertions about these things?”

“No, venerable sir, I do not see even two bhikkhus who make differing assertions about these things. But, venerable sir, there are people who live deferential towards the Blessed One who might, when he has gone, create a dispute in the Sangha about livelihood and about the Pātimokkha. Such a dispute would be for the harm and unhappiness of many, for the loss, harm, and suffering of gods and humans.”

“A dispute about livelihood or about the Pātimokkha would be trifling, Ānanda. But should a dispute arise in the Sangha about the path or the way, such a dispute would be for the harm and unhappiness of many, for the loss, harm, and suffering of gods and humans.

“There are, Ānanda, these six roots of disputes. What six? Here, Ānanda, a bhikkhu is angry and resentful. Such a bhikkhu dwells disrespectful and undeferential towards the Teacher, towards the Dhamma, and towards the Sangha, and he does not fulfil the training. A bhikkhu who dwells disrespectful and undeferential towards the Teacher, towards the Dhamma, and towards the Sangha, and who does not fulfil the training, creates a dispute in the Sangha, which would be for the harm and unhappiness of many, for the loss, harm, and suffering of gods and humans. Now if you see any such root of dispute either in yourselves or externally, you should strive to abandon that same evil root of dispute. And if you do not see any such root of dispute either in yourselves or externally, you should practise in such a way that that same evil root of dispute does not erupt in the future. Thus there is the abandoning of that evil root of dispute; thus there is the non-eruption of that evil root of dispute in the future.

“Again, a bhikkhu is contemptuous and insolent…

envious and avaricious…

fraudulent and deceitful…

has evil wishes and wrong view…

adheres to his own views, holds on to them tenaciously, and relinquishes them with difficulty. Such a bhikkhu dwells disrespectful and undeferential towards the Teacher, towards the Dhamma, and towards the Sangha, and he does not fulfil the training. A bhikkhu who dwells disrespectful and undeferential towards the Teacher, towards the Dhamma, and towards the Sangha, and who does not fulfil the training, creates a dispute in the Sangha, which would be for the harm and unhappiness of many, for the loss, harm, and suffering of gods and humans. Now if you see any such root of dispute either in yourselves or externally, you should strive to abandon that same evil root of dispute. And if you do not see any such root of dispute either in yourselves or externally, you should practise in such a way that that same evil root of dispute does not erupt in the future. Thus there is the abandoning of that evil root of dispute; thus there is the non-eruption of that evil root of dispute in the future. These are the six roots of dispute.…

Read the entire translation of Majjhima Nikāya 104 Sāmagāmasutta: At Sāmagāma by Bhikkhu Bodhi on SuttaCentral.net. Or read a different translation on SuttaCentral.net. Or listen on PaliAudio.com or SC-Voice.net. Or explore the Pali on DigitalPaliReader.online.

Or read a translation in Deutsch, Italiano, Русский, বাংলা, Español, Français, हिन्दी, Bahasa Indonesia, 日本語, မြန်မာဘာသာ, Norsk, Português, සිංහල, Slovenščina, Srpski, ไทย, Tiếng Việt, or 汉语. Learn how to find your language.

All translations on this site by Bhikkhu Bodhi are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.

Bhikkhu Bodhi, The Middle Length Discourses of the Buddha (Wisdom Publications, 2009), The Connected Discourses of the Buddha (Wisdom Publications, 2000), The Numerical Discourses of the Buddha (Wisdom Publications, 2012).

Copyright: Creative Commons Zero (CC0) To the extent possible under law, Bhikkhu Sujato has waived all copyright and related or neighboring rights to his own translations on

Copyright: Creative Commons Zero (CC0) To the extent possible under law, Bhikkhu Sujato has waived all copyright and related or neighboring rights to his own translations on

All translations on this site by Bhikkhu Bodhi are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.

Bhikkhu Bodhi, The Middle Length Discourses of the Buddha (Wisdom Publications, 2009), The Connected Discourses of the Buddha (Wisdom Publications, 2000), The Numerical Discourses of the Buddha (Wisdom Publications, 2012).

All translations on this site by Bhikkhu Bodhi are licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License.

Bhikkhu Bodhi, The Middle Length Discourses of the Buddha (Wisdom Publications, 2009), The Connected Discourses of the Buddha (Wisdom Publications, 2000), The Numerical Discourses of the Buddha (Wisdom Publications, 2012).

Translations by Bhikkhu Ṭhanissaro are released under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 Unported License. The author considers any sale, including by non-profit entities for non-profit purposes, to be ‘Commercial’ and a copyright violation. To view a copy of this license, visit the

Translations by Bhikkhu Ṭhanissaro are released under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 Unported License. The author considers any sale, including by non-profit entities for non-profit purposes, to be ‘Commercial’ and a copyright violation. To view a copy of this license, visit the