“Mendicants, these seven things that please and assist an enemy happen to an irritable woman or man. What seven?

Firstly, an enemy wishes for an enemy: ‘If only they’d become ugly!’ Why is that? Because an enemy doesn’t like to have a beautiful enemy. An irritable person, overcome and overwhelmed by anger, is ugly, even though they’re nicely bathed and anointed, with hair and beard dressed, and wearing white clothes. This is the first thing that pleases and assists an enemy which happens to an irritable woman or man.

Furthermore, an enemy wishes for an enemy: ‘If only they’d sleep badly!’ Why is that? Because an enemy doesn’t like to have an enemy who sleeps at ease. An irritable person, overcome and overwhelmed by anger, sleeps badly, even though they sleep on a couch spread with woolen covers—shag-piled, pure white, or embroidered with flowers—and spread with a fine deer hide, with a canopy above and red pillows at both ends. This is the second thing …

Furthermore, an enemy wishes for an enemy: ‘If only they don’t get all they need!’ Why is that? Because an enemy doesn’t like to have an enemy who gets all they need. When an irritable person, overcome and overwhelmed by anger, gets what they don’t need they think, ‘I’ve got what I need.’ When they get what they need they think, ‘I’ve got what I don’t need.’ When an angry person gets these things that are the exact opposite of what they need, it’s for their lasting harm and suffering. This is the third thing …

Furthermore, an enemy wishes for an enemy: ‘If only they weren’t wealthy!’ Why is that? Because an enemy doesn’t like to have an enemy who is wealthy. When a person is irritable, overcome and overwhelmed by anger, the rulers seize the legitimate wealth they’ve earned by their efforts, built up with their own hands, gathered by the sweat of their brow. This is the fourth thing …

Furthermore, an enemy wishes for an enemy: ‘If only they weren’t famous!’ Why is that? Because an enemy doesn’t like to have a famous enemy. When a person is irritable, overcome and overwhelmed by anger, any fame they have acquired by diligence falls to dust. This is the fifth thing …

Furthermore, an enemy wishes for an enemy: ‘If only they had no friends!’ Why is that? Because an enemy doesn’t like to have an enemy with friends. When a person is irritable, overcome and overwhelmed by anger, their friends and colleagues, relatives and kin avoid them from afar. This is the sixth thing …

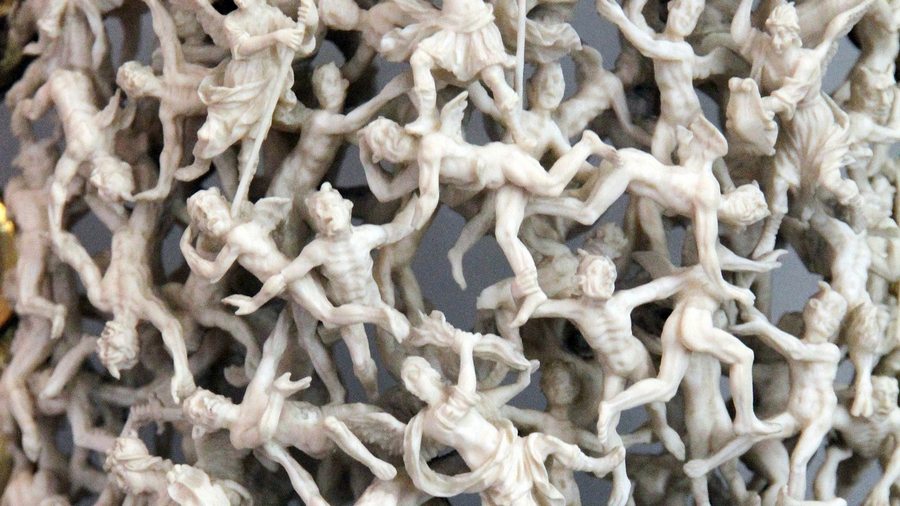

Furthermore, an enemy wishes for an enemy: ‘If only, when their body breaks up, after death, they’re reborn in a place of loss, a bad place, the underworld, hell!’ Why is that? Because an enemy doesn’t like to have an enemy who goes to a good place. When a person is irritable, overcome and overwhelmed by anger, they do bad things by way of body, speech, and mind. When their body breaks up, after death, they’re reborn in a place of loss, a bad place, the underworld, hell. This is the seventh thing that pleases and assists an enemy which happens to an irritable woman or man.

These are the seven things that please and assist an enemy which happen to an irritable woman or man.

An irritable person is ugly

and they sleep badly.

When they get what they need,

they take it to be what they don’t need.

An angry person

kills with body or speech;

overcome with anger,

they lose their wealth.

Mad with anger,

they fall into disgrace.

Family, friends, and loved ones

avoid an irritable person.

Anger creates harm;

anger upsets the mind.

That person doesn’t recognize

the danger that arises within.

An angry person doesn’t know the good.

An angry person doesn’t see the truth.

When a person is beset by anger,

only blind darkness is left.

An angry person destroys with ease

what was hard to build.

Afterwards, when the anger is spent,

they’re tormented as if burnt by fire.

Their look betrays their sulkiness

like a fire’s smoky plume.

And when their anger flares up,

they make others angry.

They have no conscience or prudence,

nor any respectful speech.

One overcome by anger

has no island refuge anywhere.

The deeds that torment a man

are far from those that are good.

I’ll explain them now;

listen to this, for it is the truth.

An angry person slays their father;

their mother, too, they slay.

An angry person slays a saint;

a normal person, too, they slay.

A man is raised by his mother,

who shows him the world.

But an angry ordinary person slays

even that good woman who gave him life.

Like oneself, all sentient beings

hold themselves most dear.

But angry people kill themselves all kinds of ways,

distraught for many reasons.

Some kill themselves with swords,

some, distraught, take poison.

Some hang themselves with rope,

or fling themselves down a mountain gorge.

When they commit deeds of destroying life

and killing themselves,

they don’t realize what they do,

for anger leads to their downfall.

The snare of death in the form of anger

lies hidden in the heart.

You should cut it out by self-control,

by wisdom, energy, and right ideas.

An astute person should cut out

this unskillful thing.

And they’d train in the teaching in just the same way,

not yielding to sulkiness.

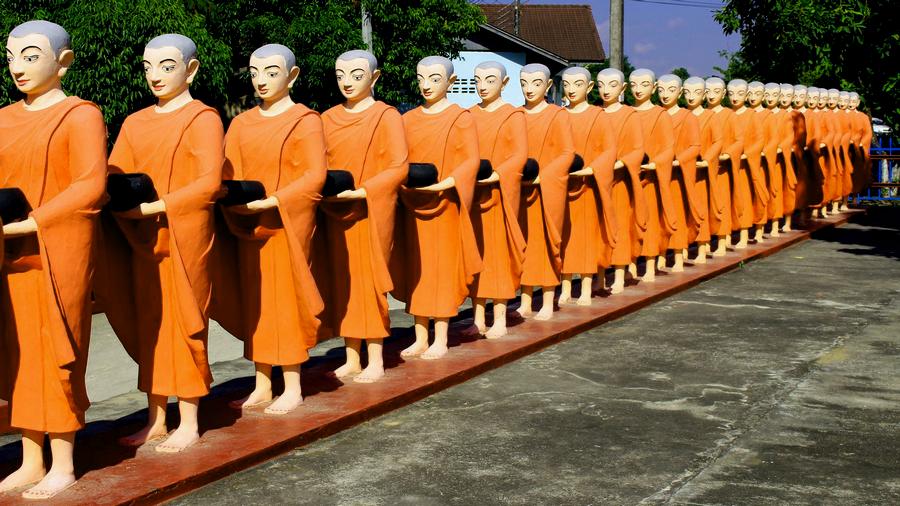

Free of anger, free of despair,

free of greed, with no more longing,

tamed, having given up anger,

the undefiled become fully extinguished.

Read this translation of Aṅguttara Nikāya 7.64 Kodhanasutta: Irritable by Bhikkhu Sujato on SuttaCentral.net. Or read a different translation on DhammaTalks.org. Or listen on SC-Voice.net. Or explore the Pali on DigitalPaliReader.online.

Or read a translation in Deutsch, Lietuvių Kalba, Русский, বাংলা, Français, Bahasa Indonesia, Italiano, 日本語, မြန်မာဘာသာ, Português, සිංහල, ไทย, Tiếng Việt, or 汉语. Learn how to find your language.

Copyright: Creative Commons Zero (CC0) To the extent possible under law, Bhikkhu Sujato has waived all copyright and related or neighboring rights to his own translations on

Copyright: Creative Commons Zero (CC0) To the extent possible under law, Bhikkhu Sujato has waived all copyright and related or neighboring rights to his own translations on