[Note: Today’s selection is unusually long, but it gives an example of the Buddha’s technique of gradual training for monastics as well as addresses the question of why some people achieve success and some do not. Finally it concludes with a reminder that not everyone ordains with the same good qualities and good intentions.]

So I have heard. At one time the Buddha was staying near Sāvatthī in the Eastern Monastery, the stilt longhouse of Migāra’s mother. Then the brahmin Moggallāna the Accountant went up to the Buddha, and exchanged greetings with him. When the greetings and polite conversation were over, he sat down to one side and said to the Buddha:

“Master Gotama, in this stilt longhouse we can see gradual progress down to the last step of the staircase. Among the brahmins we can see gradual progress in learning the chants. Among archers we can see gradual progress in archery. Among us accountants, who earn a living by accounting, we can see gradual progress in mathematics. For when we get an apprentice we first make them count: ‘One one, two twos, three threes, four fours, five fives, six sixes, seven sevens, eight eights, nine nines, ten tens.’ We even make them count up to a hundred. Is it possible to similarly describe a gradual training, gradual progress, and gradual practice in this teaching and training?”

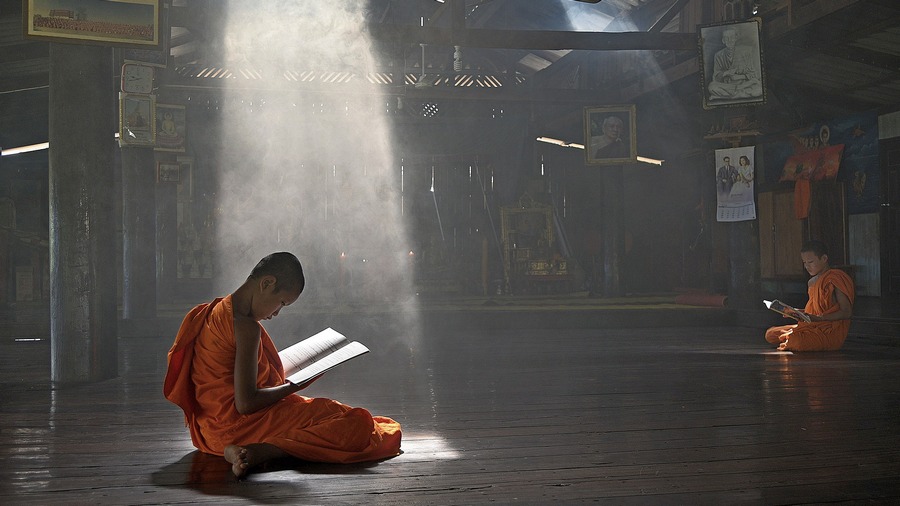

“It is possible, brahmin. Suppose a deft horse trainer were to obtain a fine thoroughbred. First of all he’d make it get used to wearing the bit. In the same way, when the Realized One gets a person for training they first guide them like this: ‘Come, mendicant, be ethical and restrained in the monastic code, conducting yourself well and seeking alms in suitable places. Seeing danger in the slightest fault, keep the rules you’ve undertaken.’

When they have ethical conduct, the Realized One guides them further: ‘Come, mendicant, guard your sense doors. When you see a sight with your eyes, don’t get caught up in the features and details. If the faculty of sight were left unrestrained, bad unskillful qualities of covetousness and displeasure would become overwhelming. For this reason, practice restraint, protect the faculty of sight, and achieve restraint over it. When you hear a sound with your ears … When you smell an odor with your nose … When you taste a flavor with your tongue … When you feel a touch with your body … When you know a thought with your mind, don’t get caught up in the features and details. If the faculty of mind were left unrestrained, bad unskillful qualities of covetousness and displeasure would become overwhelming. For this reason, practice restraint, protect the faculty of mind, and achieve its restraint.’

When they guard their sense doors, the Realized One guides them further: ‘Come, mendicant, eat in moderation. Reflect rationally on the food that you eat: ‘Not for fun, indulgence, adornment, or decoration, but only to sustain this body, to avoid harm, and to support spiritual practice. In this way, I shall put an end to old discomfort and not give rise to new discomfort, and I will live blamelessly and at ease.’

When they eat in moderation, the Realized One guides them further: ‘Come, mendicant, be committed to wakefulness. Practice walking and sitting meditation by day, purifying your mind from obstacles. In the evening, continue to practice walking and sitting meditation. In the middle of the night, lie down in the lion’s posture—on the right side, placing one foot on top of the other—mindful and aware, and focused on the time of getting up. In the last part of the night, get up and continue to practice walking and sitting meditation, purifying your mind from obstacles.’

When they are committed to wakefulness, the Realized One guides them further: ‘Come, mendicant, have mindfulness and situational awareness. Act with situational awareness when going out and coming back; when looking ahead and aside; when bending and extending the limbs; when bearing the outer robe, bowl and robes; when eating, drinking, chewing, and tasting; when urinating and defecating; when walking, standing, sitting, sleeping, waking, speaking, and keeping silent.’

When they have mindfulness and situational awareness, the Realized One guides them further: ‘Come, mendicant, frequent a secluded lodging—a wilderness, the root of a tree, a hill, a ravine, a mountain cave, a charnel ground, a forest, the open air, a heap of straw.’ And they do so.

After the meal, they return from almsround, sit down cross-legged, set their body straight, and establish mindfulness in front of them. Giving up covetousness for the world, they meditate with a heart rid of covetousness, cleansing the mind of covetousness. Giving up ill will and malevolence, they meditate with a mind rid of ill will, full of compassion for all living beings, cleansing the mind of ill will. Giving up dullness and drowsiness, they meditate with a mind rid of dullness and drowsiness, perceiving light, mindful and aware, cleansing the mind of dullness and drowsiness. Giving up restlessness and remorse, they meditate without restlessness, their mind peaceful inside, cleansing the mind of restlessness and remorse. Giving up doubt, they meditate having gone beyond doubt, not undecided about skillful qualities, cleansing the mind of doubt.

They give up these five hindrances, corruptions of the heart that weaken wisdom. Then, quite secluded from sensual pleasures, secluded from unskillful qualities, they enter and remain in the first absorption, which has the rapture and bliss born of seclusion, while placing the mind and keeping it connected. As the placing of the mind and keeping it connected are stilled, they enter and remain in the second absorption, which has the rapture and bliss born of immersion, with internal clarity and mind at one, without placing the mind and keeping it connected. And with the fading away of rapture, they enter and remain in the third absorption, where they meditate with equanimity, mindful and aware, personally experiencing the bliss of which the noble ones declare, ‘Equanimous and mindful, one meditates in bliss.’ Giving up pleasure and pain, and ending former happiness and sadness, they enter and remain in the fourth absorption, without pleasure or pain, with pure equanimity and mindfulness.

That’s how I instruct the mendicants who are trainees—who haven’t achieved their heart’s desire, but live aspiring to the supreme sanctuary from the yoke. But for those mendicants who are perfected—who have ended the defilements, completed the spiritual journey, done what had to be done, laid down the burden, achieved their own goal, utterly ended the fetters of rebirth, and are rightly freed through enlightenment—these things lead to blissful meditation in the present life, and to mindfulness and awareness.”

When he had spoken, Moggallāna the Accountant said to the Buddha, “When his disciples are instructed and advised like this by Master Gotama, do all of them achieve the ultimate goal, extinguishment, or do some of them fail?”

“Some succeed, while others fail.”

“What is the cause, Master Gotama, what is the reason why, though extinguishment is present, the path leading to extinguishment is present, and Master Gotama is present to encourage them, still some succeed while others fail?”

“Well then, brahmin, I’ll ask you about this in return, and you can answer as you like. What do you think, brahmin? Are you skilled in the road to Rājagaha?”

“Yes, I am.”

“What do you think, brahmin? Suppose a person was to come along who wanted to go to Rājagaha. He’d approach you and say: ‘Sir, I wish to go to Rājagaha. Please point out the road to Rājagaha.’ Then you’d say to them: ‘Here, mister, this road goes to Rājagaha. Go along it for a while, and you’ll see a certain village. Go along a while further, and you’ll see a certain town. Go along a while further and you’ll see Rājagaha with its delightful parks, woods, meadows, and lotus ponds.’ Instructed like this by you, they might still take the wrong road, heading west. But a second person might come with the same question and receive the same instructions. Instructed by you, they might safely arrive at Rājagaha. What is the cause, brahmin, what is the reason why, though Rājagaha is present, the path leading to Rājagaha is present, and you are there to encourage them, one person takes the wrong path and heads west, while another arrives safely at Rājagaha?”

“What can I do about that, Master Gotama? I am the one who shows the way.”

“In the same way, though extinguishment is present, the path leading to extinguishment is present, and I am present to encourage them, still some of my disciples, instructed and advised like this, achieve the ultimate goal, extinguishment, while some of them fail. What can I do about that, brahmin? The Realized One is the one who shows the way.”

When he had spoken, Moggallāna the Accountant said to the Buddha, “Master Gotama, there are those faithless people who went forth from the lay life to homelessness not out of faith but to earn a livelihood. They’re devious, deceitful, and sneaky. They’re restless, insolent, fickle, scurrilous, and loose-tongued. They do not guard their sense doors or eat in moderation, and they are not committed to wakefulness. They don’t care about the ascetic life, and don’t keenly respect the training. They’re indulgent and slack, leaders in backsliding, neglecting seclusion, lazy, and lacking energy. They’re unmindful, lacking situational awareness and immersion, with straying minds, witless and stupid. Master Gotama doesn’t live together with these.

But there are those gentlemen who went forth from the lay life to homelessness out of faith. They’re not devious, deceitful, and sneaky. They’re not restless, insolent, fickle, scurrilous, and loose-tongued. They guard their sense doors and eat in moderation, and they are committed to wakefulness. They care about the ascetic life, and keenly respect the training. They’re not indulgent or slack, nor are they leaders in backsliding, neglecting seclusion. They’re energetic and determined. They’re mindful, with situational awareness, immersion, and unified minds; wise, not stupid. Master Gotama does live together with these.

Of all kinds of fragrant root, spikenard is said to be the best. Of all kinds of fragrant heartwood, red sandalwood is said to be the best. Of all kinds of fragrant flower, jasmine is said to be the best. In the same way, Master Gotama’s advice is the best of contemporary teachings.

Excellent, Master Gotama! Excellent! As if he were righting the overturned, or revealing the hidden, or pointing out the path to the lost, or lighting a lamp in the dark so people with clear eyes can see what’s there, Master Gotama has made the Teaching clear in many ways. I go for refuge to Master Gotama, to the teaching, and to the mendicant Saṅgha. From this day forth, may Master Gotama remember me as a lay follower who has gone for refuge for life.”

Read this translation of Majjhima Nikāya 107 Gaṇakamoggallānasutta: With Moggallāna the Accountant by Bhikkhu Sujato on SuttaCentral.net.

Or read a different translation on DhammaTalks.org. Or listen on PaliAudio.com or SC-Voice.net. Or explore the Pali on DigitalPaliReader.online.

Or read a translation in Bengali, Català, Deutsch, Español, Français, Hebrew, हिन्दी, Magyar, Indonesian, Italiano, မြန်မာဘာသာ, Norsk, Português, ру́сский язы́к, සිංහල, Srpski, ไทย, Tiếng Việt, or 汉语. Learn how to find your language.