“Mendicants, there are eight causes and reasons that lead to acquiring the wisdom fundamental to the spiritual life, and to its increase, growth, and full development once it has been acquired. What eight?

1. It’s when a mendicant lives relying on the Teacher or a spiritual companion in a teacher’s role. And they set up a keen sense of conscience and prudence for them, with warmth and respect. This is the first cause.

2. When a mendicant lives relying on the Teacher or a spiritual companion in a teacher’s role—with a keen sense of conscience and prudence for them, with warmth and respect—from time to time they go and ask them questions: ‘Why, sir, does it say this? What does that mean?’ Those venerables clarify what is unclear, reveal what is obscure, and dispel doubt regarding the many doubtful matters. This is the second cause.

3. After hearing that teaching they perfect withdrawal of both body and mind. This is the third cause.

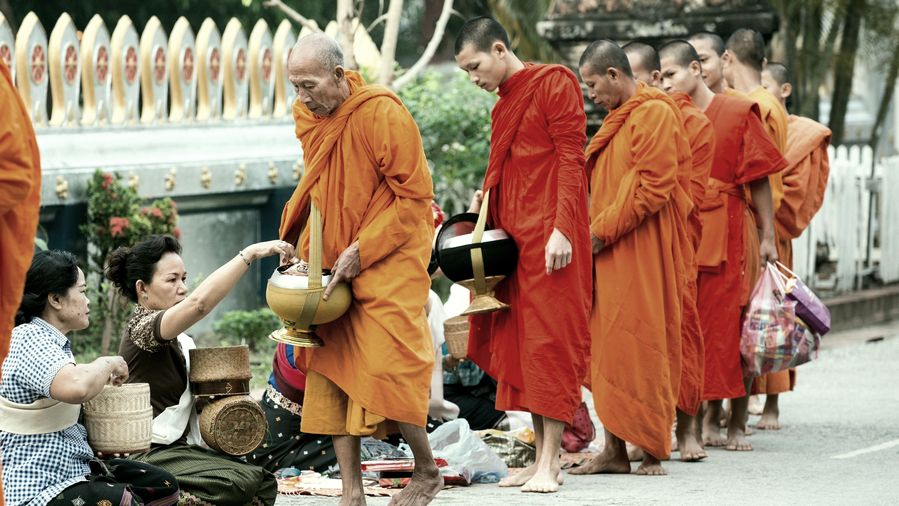

4. A mendicant is ethical, restrained in the monastic code, conducting themselves well and seeking alms in suitable places. Seeing danger in the slightest fault, they keep the rules they’ve undertaken. This is the fourth cause.

5. They’re very learned, remembering and keeping what they’ve learned. These teachings are good in the beginning, good in the middle, and good in the end, meaningful and well-phrased, describing a spiritual practice that’s entirely full and pure. They are very learned in such teachings, remembering them, reinforcing them by recitation, mentally scrutinizing them, and comprehending them theoretically. This is the fifth cause.

6. They live with energy roused up for giving up unskillful qualities and embracing skillful qualities. They’re strong, staunchly vigorous, not slacking off when it comes to developing skillful qualities. This is the sixth cause.

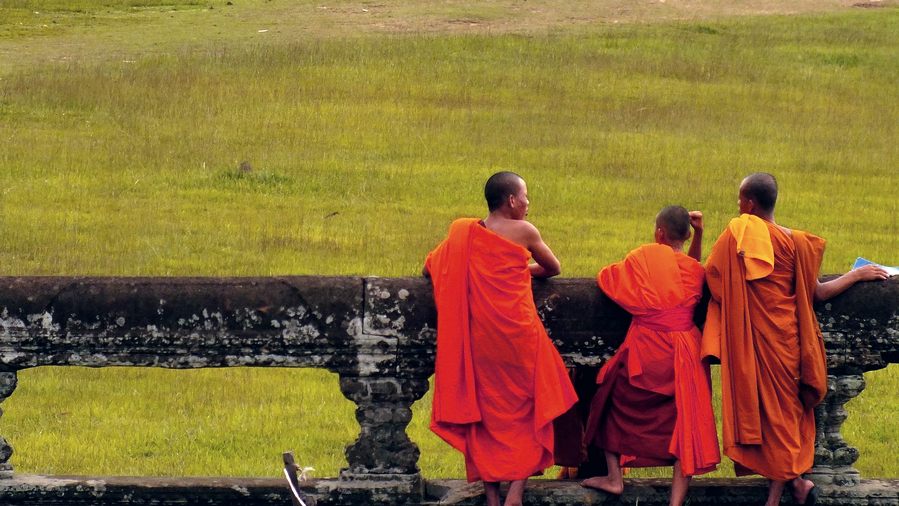

7. When in the Saṅgha they don’t engage in motley talk or low talk. Either they talk on Dhamma, or they invite someone else to do so, or they respect noble silence. This is the seventh cause.

8. They meditate observing rise and fall in the five grasping aggregates. ‘Such is form, such is the origin of form, such is the ending of form. Such is feeling, such is the origin of feeling, such is the ending of feeling. Such is perception, such is the origin of perception, such is the ending of perception. Such are choices, such is the origin of choices, such is the ending of choices. Such is consciousness, such is the origin of consciousness, such is the ending of consciousness.’ This is the eighth cause.

Their spiritual companions esteem them: ‘This venerable lives relying on the Teacher or a spiritual companion in a teacher’s role. They set up a keen sense of conscience and prudence for them, with warmth and respect. Clearly this venerable knows and sees.’ This quality leads to fondness, respect, esteem, harmony, and unity.

‘This venerable lives relying on the Teacher or a spiritual companion in a teacher’s role, and from time to time they go and ask them questions … Clearly this venerable knows and sees.’ This quality also leads to fondness, respect, esteem, harmony, and unity.

‘After hearing that teaching they perfect withdrawal of both body and mind. Clearly this venerable knows and sees.’ This quality also leads to fondness, respect, esteem, harmony, and unity.

‘This venerable is ethical … Clearly this venerable knows and sees.’ This quality also leads to fondness, respect, esteem, harmony, and unity.

‘This venerable is very learned, remembering and keeping what they’ve learned. … Clearly this venerable knows and sees.’ This quality also leads to fondness, respect, esteem, harmony, and unity.

‘This venerable lives with energy roused up … Clearly this venerable knows and sees.’ This quality also leads to fondness, respect, esteem, harmony, and unity.

‘When in the Saṅgha they don’t engage in motley talk or low talk. Either they talk on Dhamma, or they invite someone else to do so, or they respect noble silence. Clearly this venerable knows and sees.’ This quality also leads to fondness, respect, esteem, harmony, and unity.

‘They meditate observing rise and fall in the five grasping aggregates. … Clearly this venerable knows and sees.’ This quality also leads to fondness, respect, esteem, harmony, and unity.

These are the eight causes and reasons that lead to acquiring the wisdom fundamental to the spiritual life, and to its increase, growth, and full development once it has been acquired.”

Read this translation of Aṅguttara Nikāya 8.2 Paññāsutta: Wisdom by Bhikkhu Sujato on SuttaCentral.net. Or read a different translation on SuttaCentral.net or DhammaTalks.org. Or listen on SC-Voice.net. Or explore the Pali on DigitalPaliReader.online.

Or read a translation in Deutsch, Bengali, Español, Indonesian, Italiano, မြန်မာဘာသာ, Português, ру́сский язы́к, සිංහල, ไทย, Tiếng Việt, or 汉语. Learn how to find your language.